Rewiring the enemy within: why women turn on each other — and how we stop

Envy, self-policing and the ritual scapegoating of successful women

So, Glennon Doyle joined Substack. Then she left. Not because she caused harm, or said something outrageous. She left, presumably, because of all the bitching.

Everyone's writing about it. Dissecting it. And yes, you’re probably sitting there sighing Not another bloody article about Glennon. I’m really getting a bit sick and tired of it all.

But there's something specific here about women policing women – about the enemy within – that we need to look at. Especially when the criticism dressed itself up in the language of fairness and community standards.

The wave of commentary that rolled in – mostly from women – questioned her “tone”, why she'd launched behind a paywall, and why she was even here at all.

Why take up more space? Why ask people to pay, when you've already made your millions? Why come to a platform built for lesser-known voices, when yours is already everywhere, when you already have a multitude of followers, bestselling books, a chart-topping podcast?

Aren’t you satisfied with what you’ve already got?

It all sounded vaguely principled. Reasonable, even. But it wasn't about fairness or etiquette at all.

It was about envy.

But buried envy. Envy gone wonky. The kind of envy that hides in the shadows under layers of moral indignation. The kind we don't admit to ourselves, let alone anyone else.

Because for women, envy is one of the most forbidden of feelings. It's bitchy. Unsisterly. Unbecoming. So when it comes, we disguise the hell out of it.

We don't say I want what she has. We say She's greedy. She's got enough. She should leave room for others.

We use one deadly sin to distract from another. We can't be envious – so we call her greedy.

Or – not a deadly sin, but arguably even worse – she’s just being too brazen, too brassy, too bold. She’s barged in. She’s not read the room. She’s disrespected others. She’s downright rude.

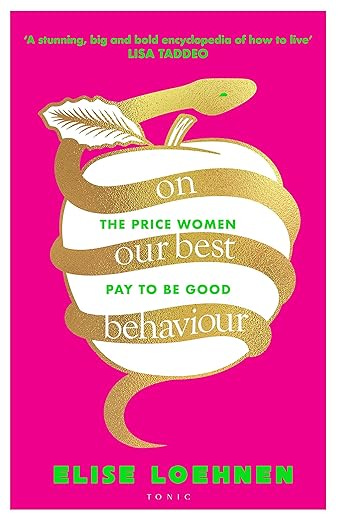

This is what Elise Loehnen writes about so brilliantly in On Our Best Behaviour. She traces how the seven deadly sins – pride, envy, greed, lust, gluttony, wrath, sloth – were never just about morality. They became tools to train women into "behaving well". Or more precisely, staying small and easy to control.

Not too hungry. Not too visible. Not too proud.

"We're programmed to believe that if someone is doing what we want to be doing, we must dethrone her," Loehnen says.

"That there's not room for all of us. It is consistent and insidious and is the basis of our instinct to bat each other down… “

“If we can stop policing each other's self-expression and 'bigness,' I think we can lean into our own."

An outbreak of women policing each other's bigness is exactly what's just happened to Glennon Doyle.

Here is a woman being too much, asking for too much, taking up too much space. And a culture of other women, all trained to keep each other in check.

And to understand how that works, we have to go back.

Not just to the seven deadly sins. But to the design of prisons.

How we learned to police ourselves

Before the modern era, control was public and brutal. You stole something, you lost your hand. You stepped out of line, and you were strung up in the square. You were a bit weird and witchy, and you were burned at the stake. Punishment was visible. Immediate. Unmistakable.

But that kind of control requires a LOT of effort. Constant force. So it evolved.

Power got clever.

In the late 1700s, philosopher Jeremy Bentham proposed a new kind of prison. A building called the Panopticon.

A ring of prison cells facing a single central watchtower. The tower has darkened glass. The prisoners can't tell if anyone is inside.

So they begin to behave as if someone is always watching.

The philosopher Michel Foucault used the Panopticon as a metaphor for modern power in his book Discipline and Punish.

When you might be seen at any time, you start policing yourself. Eventually, you don't need a guard in the tower. You become your own guard, and everyone else's.

This is exactly what has happened to women under patriarchy.

We've absorbed the rules so deeply, we enforce them without being asked or told.

We shrink ourselves before anyone tells us to. We scan our tone. We apologise for ambition. We make ourselves smaller, softer, safer.

And when another woman doesn't fall in line? When she breaks those internalised rules and refuses to shrink? When she turns up "like she owns the place"?

We lash out in judgment that feels righteous.

We don't say I'd kill for a bit of bloody Glennon's success. We say It's not her, it's her tone. I don't have a problem with her being here, but she's not respecting the community. She's not behaving correctly. She's just barged in with no regard for the rest of us.

We don't see this as the system at work inside us.

Because it feels justified, it feels reasonable, and it speaks in our voice.

Casting her out: envy, exile and the illusion of harmony

What happened to Glennon wasn't new. It has a long history – and it has always served the same purpose.

The instinct to cast someone out to relieve collective tension has ancient roots. In Athens, citizens held an annual vote to expel someone from the city – not for crimes, but for being too powerful, too popular, too opinionated, too big for their boots.

The expelled weren't chosen because they were bad.

They were chosen because they represented the collective Shadow – what we all secretly want, but cannot admit to wanting.

They became containers for the city's unspoken tensions: shame, fear, envy, pride. By casting them out, the group could feel purged. Cleansed. Rebalanced.

The Greeks had two practices for this kind of expulsion.

Ostracism was the formal civic process used in Athens. Citizens could vote to exile one individual from the city for ten years. No trial. No charges. No defence. Just names scratched onto pottery shards, and if enough votes were cast against someone, they had to leave.

Pharmakos, on the other hand, referred to a different kind of casting out. Less democratic. More symbolic. A scapegoat figure chosen to carry the sins and shadows of the community – often someone marginal or marked. They were expelled, sometimes sacrificed, in the name of purification.

One was civic. The other, ritual. But the logic was the same: expel what makes us uncomfortable, and call it "medicine".

The word pharmakos shares its root with pharmakon – meaning both poison and cure. It's where we get "pharmacy" from. The scapegoat was treated as both the problem and the remedy. The source of tension and the means to relief.

But this was never real healing. It was mass projection , sanctioned by the state. It preserved the system by targeting the one who revealed its cracks.

Today, we see the same ritual play out in public pile-ons and private group chats. In trolling and cancelling. In the schadenfreude of watching another woman fall – not because she's done something terrible, but because she's risen too high, taken up too much space, dared to succeed on her own terms.

Back then: names scratched on pottery shards. Now: comment threads and self-righteous Notes.

The technology has changed. The ritual hasn't.

The rules live in us now

In ancient Athens, scapegoating was overt. Civic. And led by men, of course.

But systems evolve.

We don't hold public rituals anymore. But the control still happens. The mechanism hasn't disappeared. It's just moved onto social media.

We've already talked about how modern power works not through overt rules, but through internalised surveillance. You start watching yourself. Correcting yourself. Staying in line. You become both the prisoner and the guard in the tower.

And now? That same logic shapes how women treat each other.

We've internalised the rules so deeply that we respond viscerally when someone else breaks them. Not because we're consciously malicious. But because we've learned that women who get too big get punished. So we subconsciously enforce the rules that have kept us safe.

And when someone refuses to follow them? When she takes up space, unapologetically? When she doesn't make herself small?

We reach for what feels fair.

She's being greedy. She's had her share. She should step back.

But what we're really doing is re-enacting the same old logic. We're still punishing someone for carrying what we're not allowed to name in ourselves.

Desire. Power. Visibility.

We've become the enforcers.

And we think we're doing the right thing.

From scapegoating to medicine: rewiring the rules that keep women small

This is how the scapegoat ritual lives on today – as digital ostracism. The purge has gone online, with the rules of patriarchy now policed by women as well as by men. When the “enemy within” is running the show, women become the very system we long to escape. Ruled by fear, scarcity, and buried envy, we turn on each other, justifying our judgments and mistaking projection for principle.

That's why rewiring ourselves matters – not as an idea, but as a practice and a choice.

Women are the Medicine isn't about fixing the world by making everything fair and equal. It's about recognising that we've internalised the system, and we’re often entirely unconscious of how it operates within us. We urgently need to wake up to what these outbreaks look like – the righteous judgment, the vitriol, the self-justification, the carefully phrased arguments for and against, the appeal to rules of "good behaviour." We need to bring this into consciousness to liberate ourselves.

Only then can we become true medicine for ourselves and each other. From the Latin medēri – to heal, to tend, to restore. Not to purge or scapegoat like pharmakos – that false cure that pushed pain elsewhere. Real medicine doesn't cast people out. It sits with discomfort, tells the truth, and doesn't exile our Shadow parts. It listens to them instead.

So next time that inner voice rises – the one that says she's taking up too much space, who does she think she is – meet it with curiosity. What's the fear beneath the judgment? What part in yourself are you disowning? That's where the system lives and where we must begin dismantling it. The seven deadly sins weren't sins but desires and hungers the system couldn't control - that’s why we were taught to fear them, and to police them in others.

Whenever you find the internet bristling at another woman's bigness, remind yourself that we can't become medicine for others until we become it for ourselves – recognising and owning our exiled hungers not as failings, but as signals of what we've been told we can't want. Without this work, we'll keep projecting outward, policing other women, and mistaking our fear for fairness.

And that's how patriarchy survives – not through force, but through our unconscious obedience to its invisible rules.

The master's tools will never dismantle the master's house.

– Audre Lorde

If we don't become more aware – if we don't take responsibility for rewiring the enemy within – then we remain the master's tools. Not metaphorically. Literally. We become the mechanism by which the system maintains itself.

We don't dismantle it by playing by its rules. We dismantle it by doing the work the system depends on us avoiding. By turning toward the parts of ourselves – envy, greed, ambition – we were taught to exile. And by refusing to cast them out in others.

The next time you see the internet blowing up at another woman's bigness, ask what part of us has been trained to stay small. Because when we stop policing each other, perhaps then we can all finally take up the space we deserve.

Agree, it is about seeing and recognizing where we have internalized patriarchy and how we police other women. I can say, even carry out misogyny.

Interesting. I hadn’t heard about the Glennon Doyle debacle. I have seen grumbles about ‘another big name’ coming to Substack though.

Thanks for the book recommendation, I’ve downloaded a copy.